Motivation

When reversing or fuzzing an executable, being able to run an arbitrary function with controlled data is extremely helpful. Through iteratively playing with the function’s parameters and examining the output, we can better understand the function’s logic.

Background

A dll (Dynamic Linked Library) with our target function would allow us to conveniently review and test the function as we wish. The only problem is that usually the function we want to examine resides in an exe, not a dll. Converting¹ an exe to a dll is a solvable challenge. After all, both an exe and a dll share the same [PE \(Portable Executable\) file format](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portable_Executable). So let’s explore, how can we convert¹ an exe to a dll?

Spoiler: there are a few more steps than just changing the extension 😉

¹ “convert to DLL” = fundamentally behave like a DLL.

I’ll use this exe created from the following code and target the decode_string function for demonstration purposes throughout this post.

#include <stdio.h>

void decode_string(char * s)

/* Function decodes string s */

{

while(*s)

{

*s = s[0] ^ 0x31 ^ s[1];

s++;

}

}

void main()

{

char s[] = "\x51\x08\x5c\x01\x5c\x02\x13\x18";

decode_string(s);

printf("%s\n", s);

printf("done\n");

}

Challenges

There are 2 primary areas we need to change when converting an exe to a dll:

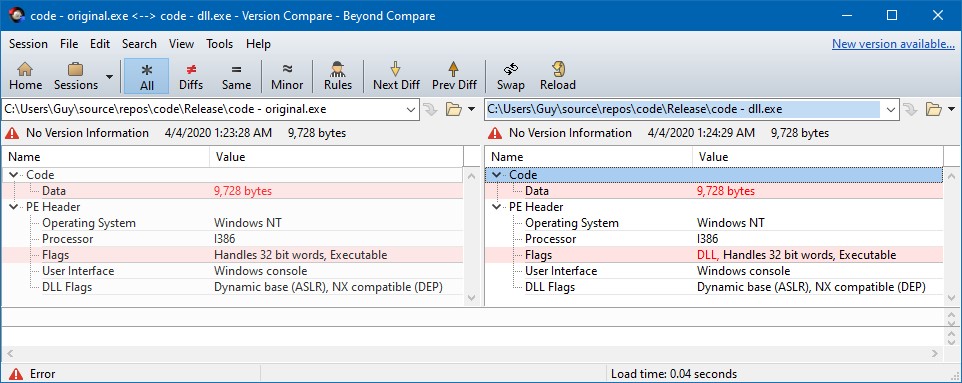

- File Header - Both file types have the same PE header format, but there is one specific flag that is unique to dlls. This is discussed later in detail.

- Entry Point Code - Both file types have code that run once the file is loaded, but there are fundamental differences (in the purpose, integration, and structure) of that code between the two files types. This is also discussed in detail later on.

Step 1: Modify The File Header

The OS differentiates between an exe and a dll by their “Characteristics” field in the PE header. A dll has the IMAGE_FILE_DLL (0x2000) flag set, while an exe doesn’t. So to solve our first problem, we’ll turn this flag on.

This handy python script turns on the IMAGE_FILE_DLL flag of a PE. Alternatively, you can use your favorite PE editor to do so. Turning on the IMAGE_FILE_DLL flag on our example exe will result in this file.

Step 2: Patch The Entry Point

After a PE file is loaded, the file’s entry point code is executed, which is set by the AddressOfEntryPoint field in the PE header. For exe files, the entry point is wrapper code that calls the “main” function, but for dll files, the entry point is the “DllMain” function that behaves differently.

The main() and DllMain() functions have 3 significant differences (as mentioned earlier in challenge #2) that must be overcome for our modified exe to successfully load like a dll:

Purpose

main()’s purpose is to perform and manage the core functionality of the executable. However, DllMain’s purpose is to only perform minimal initialization and then return immediately.

Return Value

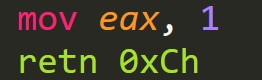

A successful exit from main() is indicated by returning 0. Conversely, a successful exit from DllMain() is True (any non-zero value). If DllMain() returns False (0) when we try to load it, the OS fails the load with error code 1114 “A dynamic link library (DLL) initialization routine failed.”

Function Prototype

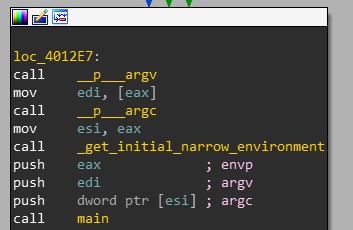

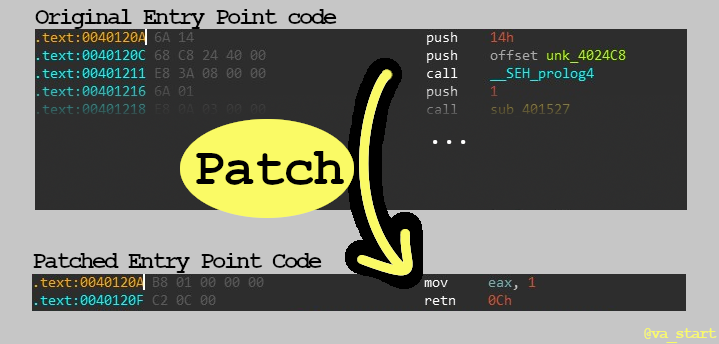

The entry point of a .exe isn’t called with any parameters on the stack. Instead, the code at the entry point that wraps main() uses Windows functions to prepare main()’s arguments (argv, argc, and envp) as seen in Figure 2:

This is not the case for DllMain. DllMain is given 3 parameters (hinstDLL, fdwReason, lpvReserved), which it must clean from the stack before returning, according to its stdcall calling convention, to ensure stable code continuation.

The Patch

The good news is we can correct these 3 discrepancies between the exe and dll entry points with one simple patch: overwrite the code in the exe entry point to simply “return 1”.

This patch changes the Entry Point code to “return immediately with a successful code and clean the stack variables.”

After this step, we are done patching the target file :). We will now focus on writing the code invoking the call to our new “DLL”.

Step 3: Invoke The Call

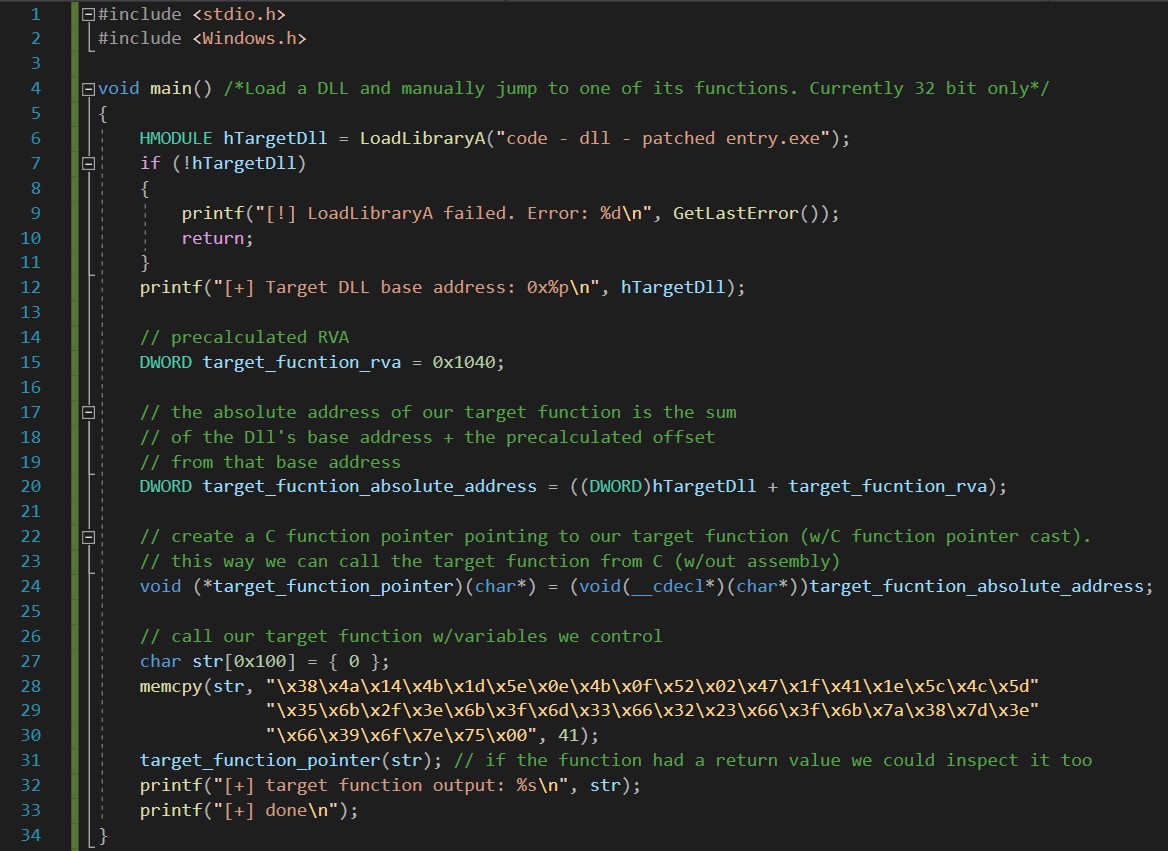

Now that we have a file that behaves like a DLL, we can load it with LoadLibrary(). LoadLibrary() will load our modified exe into our process’s address space and run the Entry Point code.

Calculating RVA

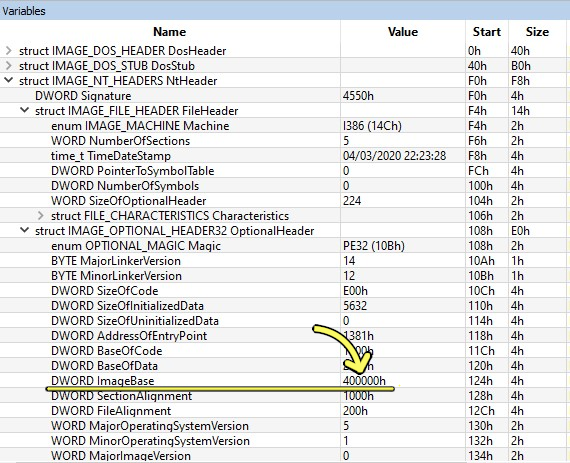

Next, to call our target function we need to calculate its RVA (Relative Virtual Address), the function’s offset from the base of the file. This is done by simply subtracting the function’s offset (the address as it appears in IDA) from the program’s Image Base (can be found using any PE viewer).

As seen in Figure 5 above, my example exe’s image base is 0x400000.

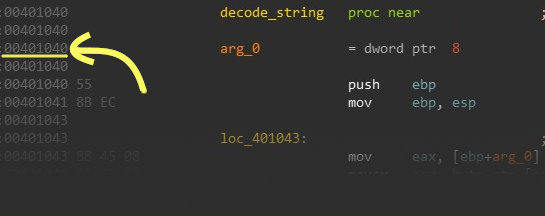

And as seen in Figure 6, my target function’s offset is 0x401040.

By subtracting the Image Base form the target function’s offset we compute that the function’s RVA = 0x401040 - 0x400000 = 0x1040.

Finally, all that’s left is performing a call to LoadLibrary() and applying confusing C function pointer syntax to call the target function. If our exe were more complex, we would probably need additional calls before directly calling the target function - see the Improving Implementation section below. However, with this simple example exe, we are all done.

Click the image below to enlarge it or view the code on Github here. I was extra verbose with comments to explain exactly what each line does.

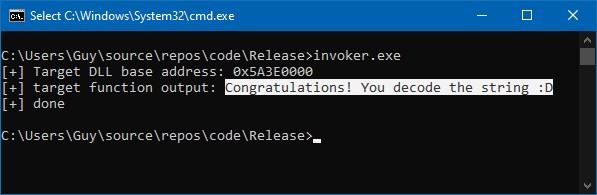

And here is the result running the code:

Yay! Success! We hacked our .exe file into a .dll, and successfully ran a function from it.

Closing Notes

I hope you enjoyed learning a new trick, patching a .exe to use as a .dll with LoadLibrary, to run arbitrary functions in executables!

Thank you Ben for helping me write and review this post! Follow him on Twitter @B_H101 for infosec tweets.

Self plug: Follow me on Twitter @mavlevin for new blog posts and infosec tweets too.

Improving Implementation

Something I didn’t mention in this post for the sake of brevity is that usually complex programs have some initialization done before they reach certain functions. For example, a logging function might expect the computer’s hostname to be in a certain global variable before it runs, and will crash if it’s not.

To prevent breaking the code like that, we need to allow the initialization code to run. The easiest way to do this is finding the function that performs the initialization, and then directly calling that function before calling the real target function. You can leave a comment on this post or reach me on Twitter if you have any questions or comments.