Every 12 seconds, risk-free profit is auctioned for millions on the Ethereum network. It’s a brutal, PvP fight. The miners take the majority of the profit, and the traders fight for the scraps.

But while staring at the auction source code at 3 am, I found a way to beat the house.

I found a “digital sleight of hand” vulnerability, a race condition hidden in the milliseconds between database calls. If I timed it right, I didn’t have to pay to win the auction. I could just take the prize.

This blog post builds the technical background to understand the vulnerability, followed by my personal account finding and reporting the bug in 2023.

Prize: Risk-Free Profitable Trades

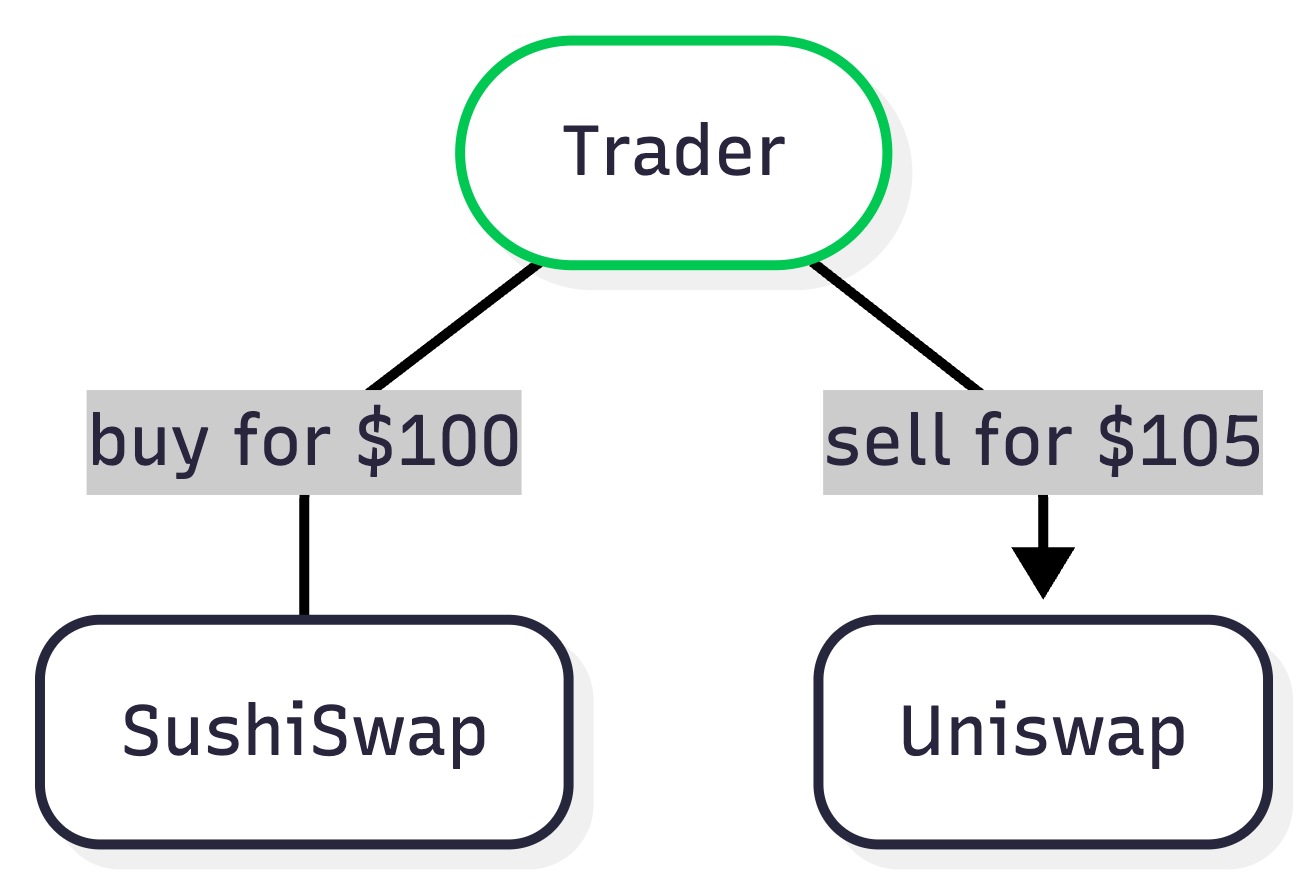

In this heist, we’re stealing the right to perform risk-free arbitrage. Consider a concrete example of an on-chain arbitrage opportunity:

- On Uniswap Exchange, Token A is trading for $100 USDC.

- On SushiSwap Exchange, the same Token A is trading for $105 USDC.

You can buy the token on Uniswap and sell it on SushiSwap for a risk-free $5 profit.

But there is a catch. Thousands of other trading bots see the exact same opportunity.

In traditional finance, this is a race of speed. High-frequency trading firms invest millions in specialized hardware to shave nanoseconds off their trading time. If their trade arrives 1ms faster, they win.

Ethereum is different. In a 12-second digital eternity, milliseconds don’t matter. You win the trade by bidding for it. But today, we’re going to steal it ;).

Auction House

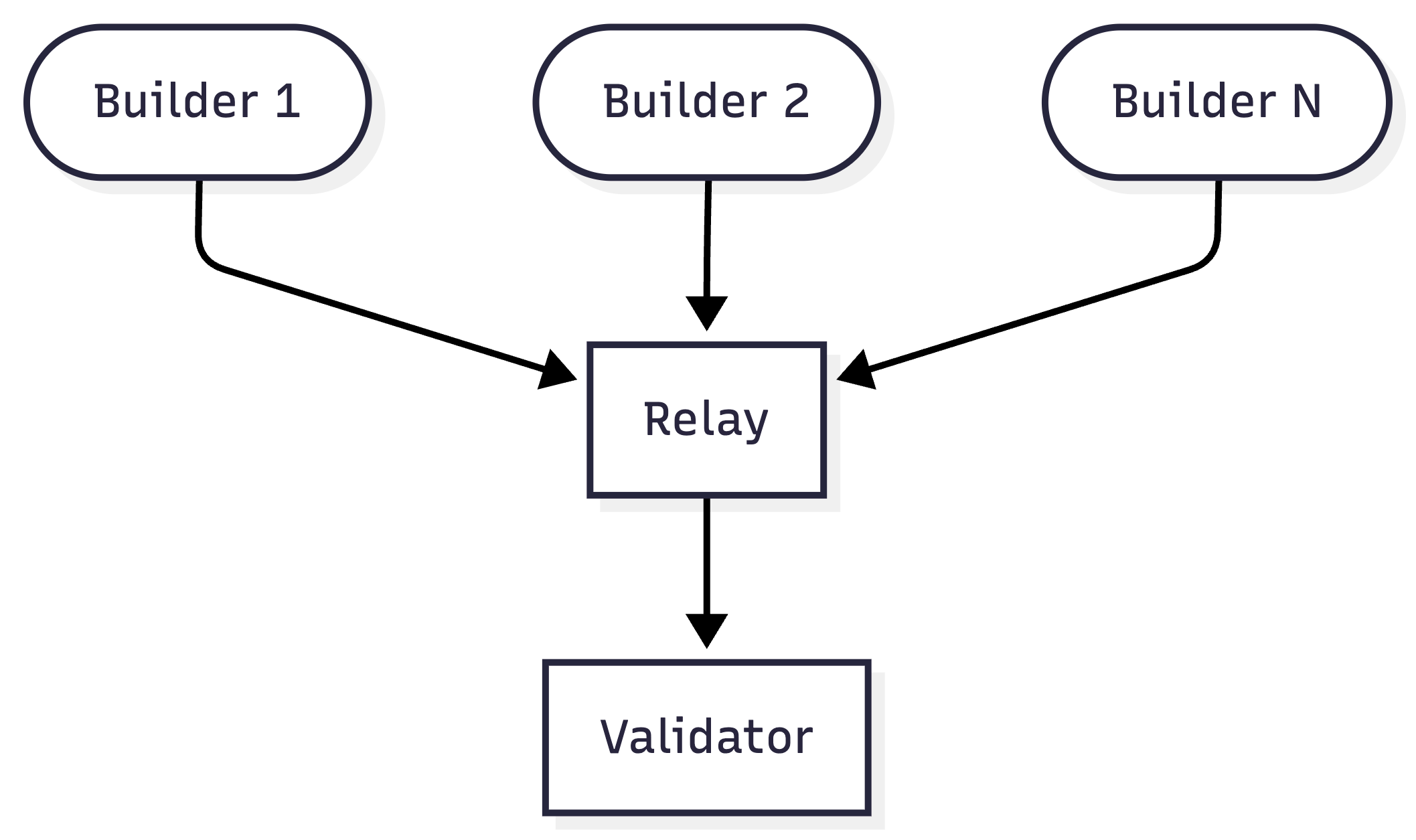

In Ethereum, Validators (previously “miners”) are randomly selected every 12 seconds to add blocks to the chain. Each block includes roughly 300 transactions. If your transaction makes it into the block, it’s executed and saved on the blockchain. Otherwise, the transaction is forgotten as if it were never sent.

So how do you get your transaction to be among the lucky 300? Money. You bid for a spot in an auction, bribing the Validator that’s building the block.

You might bid $4.50 of that $5 profit just to secure the spot. You profit $0.50, while the Validator profits $4.50.

This bidding system is called Proposer-Builder Separation (PBS). It creates a delicate supply chain. Here’s a simplified view:

- The Builder: The trader, sends transactions and attaches a bid.

- The Relay: The trusted auctioneer, identifies the transactions with the highest bid from all builders.

- The Validator (Previously “Miner”): Asks the relay for the winning transactions and adds them to the blockchain.

In practice, for large arbitrage trades, most of the profit does not go to the trader. Competitive bidding can push 90% of the arbitrage profit to the Validator.

But what if you could win the auction without paying the bid ;)? In a large trade, you would capture the Validator’s share, converting a standard arbitrage into a multi-million-dollar windfall. That is what this vulnerability enabled.

“Check-then-Act” Vulnerability

When a Trader submits transactions to the Relay, the Relay recalculates the latest “Top Bid” (the current winner). It did this in two steps using Redis.

datastore/redis.go:

func (r *RedisCache) UpdateTopBid(slot uint64, ... ) (err error) {

// Step 0:

// CONTEXT: Relay has simulated running all the blocks,

// and has calculated the Validator's payout for each, saving this information

// Step 1:

// THE CHECK: Relay reads database to find the block with the highest bid

bidValueMap, err := r.client.HGetAll(context.Background(), keyBidValues).Result()

// ... logic calculates that "Builder X" is the winner ...

// Step 2:

// THE GRAB: Relay asks Redis for Builder X's most recent payload

// (DANGER: RACE CONDITION HERE)

bidStr, err := r.client.HGet(context.Background(), keyBid, topBidBuilderPubkey).Result()

// Step 3:

// THE COMMIT: Relay saves whatever it found in step [2] as the "Top Bid"

return r.client.Set(context.Background(), keyTopBid, bidStr, expiryBidCache).Err()

}

The code assumes the payload at step 2 matches the value validated at step 1. But in between step 1 and 2, there’s a minute timing gap where a trader could switch their most recent payload.

Exploit: The Bait and Switch

Acting as the attacker, a malicious Builder/Trader, you control when you send data to the Relay. You can race the Relay’s own code against itself. You just need to be faster than the Redis round-trip in step [2] to win the bid for free.

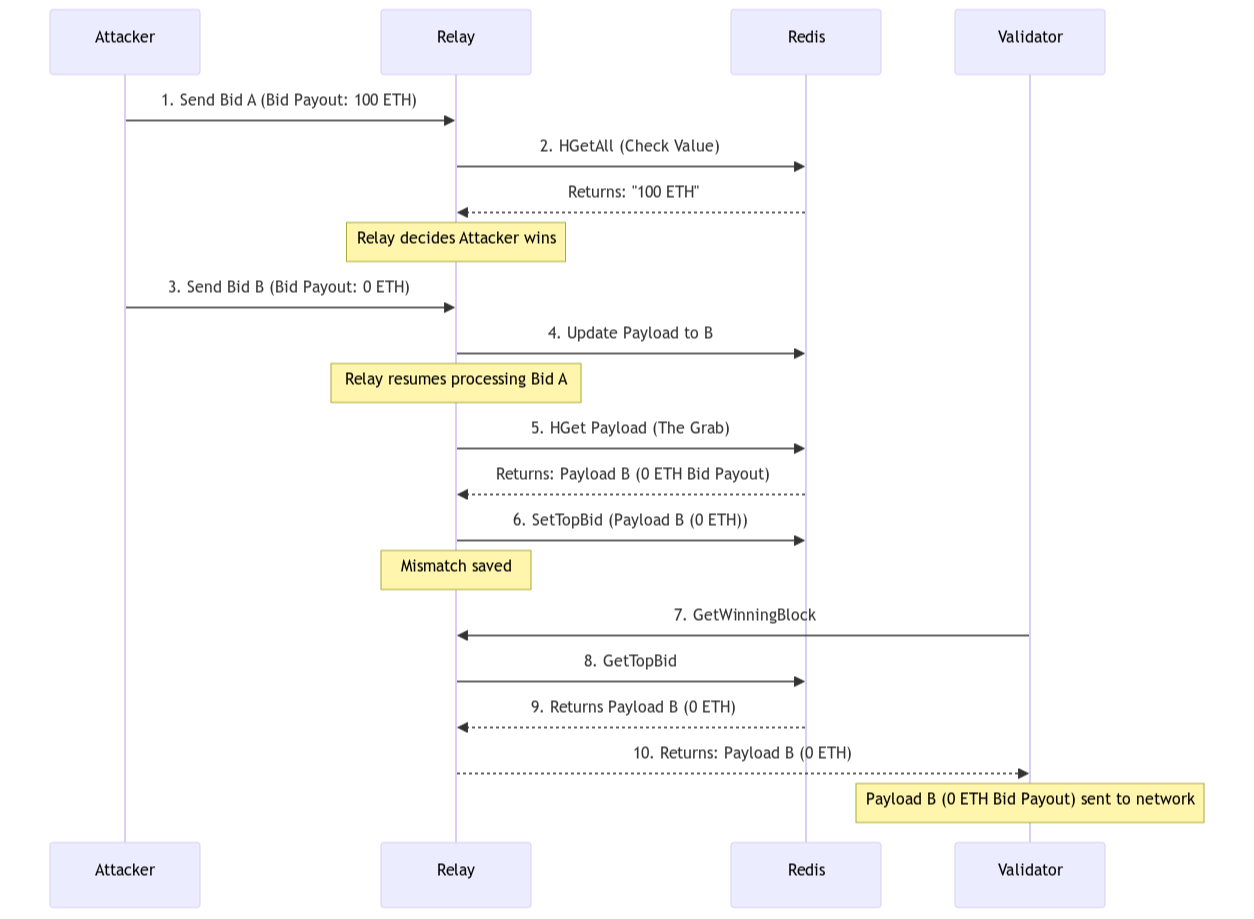

The Attack Flow:

1. The Bait (Time: T+0)

You send a valid block with a massive bid (100 ETH). This ensures you’re the highest bidder. The Relay receives it, parses it, and begins executing Step 1. It sees the 100 ETH. It marks you as the auction winner.

2. The Switch (Time: T+1)

Immediately after the first request, you flood the server with a second request. This time, the bid is 0 ETH. Your “latest payload” has been updated.

3. The Grab (Time: T+2)

The Relay, still processing the first request, finally reaches Step 2. It thinks: “Okay, the winner is Builder <you> with 100 ETH. Let me fetch their most recent payload.”

The Relay queries Redis. But you have already overwritten the data. The Relay unknowingly grabs the new, cheap payload but associates it with the old, expensive bid.

4. The Result

The Relay wraps the low-payout payload from step 2 in the expensive wrapper and sends it to the Validator. The Validator sees a header promising 100 ETH. They sign it, locking it into the blockchain.

When the block is revealed, the Validator expects a fortune. Instead, they get nothing.

You win the auction. Your transactions are included and you didn’t pay the auction. You beat the house.

The exploit I outlined here is possible, but not reliable. However, it can be performed optimistically using bids the trader is actually willing to pay in cases the exploit fails. In the worst case, the trader pays the bid they would have anyway. In the best case, they win the auction for free.

Patching to Atomic Auctions

I reported this vulnerability to the Flashbots team. They confirmed the race condition and deployed a patch almost immediately.

The fix was simple in retrospect: Atomicity. Instead of a “Check then Fetch” workflow, the new logic uses the Redis COPY command. This forces the database to handle the verification and the data movement in a single atomic operation.

The Relay tells Redis: “If this builder is the winner, copy their payload to the “winner slot” instantly.”

By removing the gap between the check and the use, the race condition is closed. You can’t swap the box if the auctioneer teleports it to the safe.

Personal Point of View

I was initially looking through this code because of the research I was doing with Professor Dan Boneh. But at 3 am, cramming in research during the last week of the quarter, I came across the UpdateTopBid function. Its implementation stumped me. It contradicted the mental model I’ve built of how the relay worked.

My mental model had recorded the relay supports concurrent requests, and for performance reasons, did so without locks. From here follows operations on cross-function resources had to be atomic; this wasn’t! Either I missed a concurrency check upstream or downstream, misunderstood the code model, was way out of touch (from unknown unknowns), or I found a vulnerability in a system transacting billions monthly.

I followed my curiosity. I needed to know if I was wrong, or if the code was wrong. I carefully tracked the control flow from an attacker’s request through the lowest level of execution, following the memory moving between structs and functions.

The vulnerability was valid. I was ecstatic from the intellectual stimulation and thrill of the chase. In the spirit of academic research, I wrote an overly academic vulnerability disclosure which Professor Boneh forwarded to the Flashbots team. The bug was immediately patched and I was rewarded a $5,000 bounty for this finding. As a college student at the time, this was a huge deal and helped fund my research into further zero-day vulnerabilities.

Thank you to Dan Boneh and the Flashbots Team.