Overview

This is Part 1 in a 4 part series about my process hunting for vulnerabilities in a network auditing tool (used to protect networks by detecting and fixing security holes) and fully exploiting one of the vulnerabilities I found. I recommend reading the series in ascending numeric order. Links to parts 2, 3, and 4 at the end of this post.

Target

I decided to look for (and successfully found) vulnerabilities in network security tool, as a vulnerability in such a tool could allow attackers to hide themselves in an otherwise secure network, or even be exploited for lateral movement.

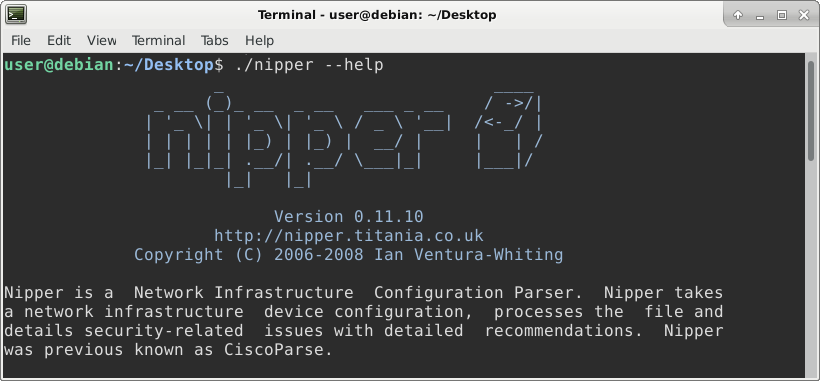

One such network security tool that came to mind is Nipper-ng, a firewall security auditing tool and firewall configuration parser. In addition to being a security product itself, Nipper-ng is used behind the scenes in other security products such as ManageEngine’s OpManager and Firewall Analyzer. The tool is also included in all installations of Kali Linux, a penetration-testing oriented Linux distribution.

Exploitation Scenario

Nipper-ng can be exploited if after an attacker gains access to a firewall in a network, when the firewall is audited, the attacker passes a malicious configuration file instead of the original one. The malicious configuration file can have a weaponized exploit (we’ll see a weaponized configuration file later in the blog series), which when parsed by nipper-ng will run code on the auditing machine! An invaluable win for the attacker, and a devastating loss for the defender, who now has the attackers code running on his or her computer.

Vulnerability Hunting Methodology

Manual Analysis

After concluding that the most exposed attack surface is parsing a firewall configuration file an attacker controls, I moved on to examining the code that parses this input.

When hunting for vulnerabilities in a new codebase, the first thing I do is skim over the code to get a general idea of the code’s style and the security practices followed. Specifically when skimming C/C++ code I take notice of:

- If buffers containing cryptographic secrets are zeroed after their use. This is considered best practice as even if an attacker successfully gains control of a program, it will be impossible to recover important secrets after they’re erased. Seeing this best practice being followed in a codebase is indicative of the security awareness of the programmer(s).

- If the return values from each function (such as malloc) are religiously checked for errors. Although unlikely under normal circumstances, a malicious adversary can cause malloc to fail (and return NULL) through exhausting the process’s memory. Forgetting this simple yet important check can easily lead to NULL pointer deference vulnerabilities (if the returned NULL value is later used) which reflects the codebases’s security.

- If “ugly” pointer arithmetic is common in the code. Pointer arithmetic is always a dangerous game as it exposes room for out of bounds access vulnerabilities. The more pointer arithmetic in the code, the more room for vulnerabilities making the code less secure.

After forming an impression of the codebase’s patterns and mapping out the attack surface, I look for vulnerabilities that can be triggered from input I control. In the case of Nipper-ng, that means looking at functions that parse the firewall configuration file.

Fuzzing

When there is a lot of code to audit, running a fuzzer can be extremely useful in finding bugs in hard to see edge cases that might otherwise be overlooked in manual review. I used honggfuzz to fuzz against nipper-ng with slight code modifications. I ran the fuzzer for a day which resulted in 10 Million fuzz iterations achieving 57 crashes stemming from 2 unique vulnerabilities. I will describe the fuzzing process and setup in more detail in a future blog post (blog post #4).

Results

Summarized below are the vulnerabilities I found and reported. Each vulnerability is described in detail in one of the following parts of the blog post series.

CVE-2019-17424

A Stack Overflow Vulnerability in the processPrivilage() function in process-general.c.

CVE-2019-17425

A Heap Overflow Vulnerability in the htmlFriendly() function in nipper-common.c

CVE-2019-17422

Null Dereference Vulnerability in the processLine() function in process-line.c

CVE-2019-17423

Uninitialized variable usage leading to DOS in processLine() function in process-line.c

Vulnerability hunting only the Cisco firewall parser’s code surfaced these 4 vulnerabilities that I have decided to disclose at this time. I found other vulnerabilities in the Cisco firewall parsing, but none that could easily lead to RCE. It is left as an exercise to the reader to find the remaining vulnerabilities.

Vendor Response and Patch

I had the pleasure of talking with the wonderful support team of the company that created nipper-ng, Titania, and also directly with Titania’s friendly and professional, founder and CEO Ian Whiting. Although nipper-ng is still used as-is and is also embedded in other products, I was informed that the company no longer supports nipper-ng and won’t issue a patch. Instead, they recommend updating to a redesigned version of nipper that can be found on their site and has a free trial period. To protect users I have decided to create patches myself for the vulnerabilities I have found that can lead to RCE (CVE-2019-17424 and CVE-2019-17425). I’ll provide a link to the patches next post.

Next Chapters

This is Part 1 in a 4 part series about my process hunting for vulnerabilities in a network auditing tool and fully exploiting one of the vulnerabilities I found. I recommend reading the series in ascending numeric order.

- Attacking The Network’s Security Core - Hunting For Vulnerabilities In A Network Security Tool (this)

- Stack Overflow CVE-2019-17424 Vulnerability Write-Up and RCE Exploit Walk Through

- Heap Overflow CVE-2019-17425 Vulnerability Write-Up and Information Leak Exploit Explained (coming soon)

- Fuzzing A Network Security Product - Finding CVE-2019-17422 & CVE-2019-17423 With The HonggFuzz Fuzzer (coming soon)